Shylock: I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following; but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you.

I watched this movie with a Korean friend of mine, and she understood it all perfectly. Actions speak louder than words, actions are easier to understand because they reveal our true intentions, and although the words of this film are poetic, the actions (and intentions) of this film offer insights into ourselves and our world in this day. We do well to give our attention to these dramas. In so doing we may learn of our own intentions, or what they might be.

Shylock: He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million, laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies; and what's his reason? I am a Jew.

It's rare that a movie bears the breast as bravely as this one does. It's insightful, because you find yourself asking, "What are they doing?", and then you realise, the movie is following our world a few hundred years ago. Things have changed, or have they?

Pacino is brilliant as a greedy and vengeful moneylender. Yet some of his anger resonates.

Shylock: I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

Personally I did not feel the pangs of anger that others who are not Christians might have felt, such as Muslims, and perhaps some Jews. I did not feel it was as much an idictment of Jews as it was a portrayal, and perhaps with some tongue in cheek, because this play was first intended to be a parody, of Christians. Christians as perfect and saintly (and kissing one another) and unindictable (if there is such a word). For me it was less about tribalism and more about desires (for wealth and love)and greed (for revenge and more wealth) and passion (for the satisfaction of these desires).

Bassanio: So may the outward shows be least themselves: The world is still deceived with ornament.

If the world has people as brave and noble as the Merchant, then we ought to have laws to protect them, and intelligent practioners to enforce them. Perhaps we do. Perhaps Fitzgerald is such a man. Unfortunately, noble merchants are few and far between, and the few that are in vogue satisfy their own egos in ways that aren't noble or brave. I'm referring to guys like Trump in The Apprentice. There is little legal apparatus left for (poor)ordinary citizens to relie on. Justice has to be bought, and it comes at a price few can afford. We do have our common sense, and Bassanio, in the persona of the woman dressed as a learned man, a symbol of our intuition (as explored in The Da Vinci Code)and that may well deliver us from evil.

Shakespeare does have a gift for revealing classical subtleties in life, in unsubtle ways. He has that gift for drammatising some of our secret moral daydreams.

In this film you'll see breasts hanging out of dresses, because that's how the prostitutes revealed themselves, and woed their clients. Are we so much more civilised today?

You see a man kiss a man on the lips, and a goat's throat being slit - if you don't duck, it seems, that blood might fall from the screen and spray onto you in your seat. There's more, and it seems a shame that Shakespeare is not here, to reveal and mock the subtleties and not so subtleties of our ridiculous lives and even more ridiculous governments. Or perhaps he is, in a different guise.

Most interesting is how our own words and intentions condemn or liberate us. We see this in the so-called 'war on terror'.

Shylock: If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villany you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

So we see our revenge for 9/11 dealt on the Middle East in Iraq, and they will learn their revenge, and have their revenge on West.

When we see Shylock and the Merchant intersect, the one with his knife, the other with his body lashed to a chair, and his clothes torn open, it is interesting how the fate of man can rest on the edge of a blade. The pity is ours that there are so few to know the wisdom that is our wisdom.

Controversial, compelling 'Merchant of Venice'

Julian Satterthwaite / Daily Yomiuri Staff Writer

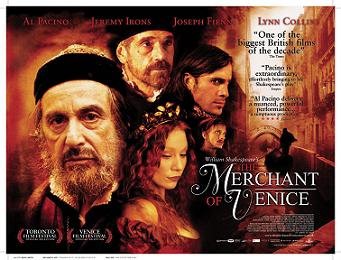

Macbeth has been adapted for the cinema at least 18 times, according to movie database imdb.com. Othello has been done at least 12 times and King Lear at least eight. But only now has The Merchant of Venice made it to movie theaters, and you don't have to look far to understand why one of Shakespeare's best-known plays has also proved one of the hardest to adapt.

"It's never been done as a movie...probably because it was too controversial," says British director Michael Radford, addressing the inevitable question of whether the play, and now his movie, are anti-Semitic.

The charge concerns the character of Shylock, here played by Al Pacino. A Jewish moneylender in medieval Venice, Shylock extends a loan to Christian nobleman Antonio (Jeremy Irons) on condition that he make good any forfeit with a pound of his own flesh. When Antonio's boats quite literally fail to come in, Shylock demands payment in full--even though it will cost Antonio his life.

Vengeful and relentless in his insistence that Antonio honor his contract, Shylock is sometimes seen as a racist stereotype of the avaricious, slightly subhuman Jew.

Not surprisingly, Radford rejects the charge. "It's a 21st-century perception of things," he says of the play's critics. "Nobody who could write those great speeches that Shylock had could be an anti-Semite."

Certainly, the movie Merchant takes pains to make Shylock a tragic character--the most common modern interpretation of a man previously played as either utter villain or comic buffoon.

In a short prologue, Radford adds a scene where Antonio is seen spitting on Shylock--illustrating a standard, shameful practice among Christians of the time. A series of captions also explain that anti-Semitism was then the norm, leaving the audience in no doubt that this Shylock is tragic victim, not a monster. His behavior may be regrettable, but it is the sad consequence of prejudice, not an example of it.

Doubts remain about the play's original intent. Shakespeare invites us to cheer as Shylock is reduced to ruin (and forced to convert to Christianity) in the famous trial scene near the end. And he never loses an opportunity to have supporting characters damn the moneylender, even while Antonio is never portrayed as less than saintly.

Even so, the Shylock seen here is one that will resonate with modern audiences. Radford claims, perfectly plausibly, that some Muslim viewers have seen his movie as being about the difficulties they face in an era of Islamophobia.

Pacino's riveting performance also helps. Despite some hammy showings in recent years, here he is full of subtlety and, if anything, is rather understated.

Overcoming charges of anti-Semitism is not the only challenge in adapting Merchant of Venice, however. Any version of the play also has to balance the two wildly different strands of the story--Shylock's tragedy and the light romantic comedy of Portia and Bassanio. "I think what happened was he [Shakespeare] intended to write a comedy and then got intrigued by this character [Shylock]," Radford says, explaining the contrary nature of the two plots.

In the movie version, the serious side of the play certainly wins out, with the director playing up some of the complexities that have usually been left implicit.

"One is Antonio's unrequited love for Bassanio, his homosexual love," Radford says. "I happen to think it's a true homosexual love affair...If you don't have that in there, what is it all about?"

It's an analysis that adds extra depth to Irons' fey, melancholy performance as Antonio--a character who can sometimes seem little more than a cipher for nobility. "In sooth I know not why I am so sad," Antonio says in the movie's opening line, but the audience soon does.

Radford says he set out to create a version of Shakespeare that was "lucid, clear and involving." He succeeds with a film that draws viewers in from its opening frames. Give your ear a few minutes to adjust to the Shakespearean dialogue and this is a compelling, very modern drama full of contemporary themes.

"People went to Shakespeare's plays in their thousands in the 16th century...and they didn't speak in verse in those days either, so what was it that got them there?" Radford asks. "It was the story."

No comments:

Post a Comment