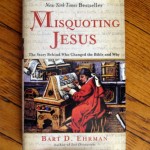

How often do we hear people “explaining” religious beliefs by stating ”The Bible says so,” as if the Bible fell out of the sky, pre-translated to English by God Himself? It’s not that simple, according to an impressive and clearly-written book that should be required reading for anyone who claims to know “what the Bible says.”

The 2005 bestseller, Misquoting Jesus, was not written by a raving atheist. Rather, it was written by a fellow who had a born-again experience in high school, then went on to attend the ultraconservative Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. Bart Ehrman didn’t stop there, however. He wanted to become an evangelical voice with credentials that would enable him to teach in secular settings. It was for this reason that he continued his education at Wheaton and, eventually, Princeton, picking up the ability to read the New Testament in its original Greek in the process.

As a result of his disciplined study, Ehrman increasingly questioned the fundamentalist approach that the “Bible is the inerrant Word of God. It contains no mistakes.” Through his studies, Ehrman determined that the Bible was not free of mistakes:

We have only error ridden copies, and the vast majority of these are centuries removed from the originals and different from them, evidently, in thousands of ways.(Page 7). At Princeton, Ehrman learned that mistakes had been made in the copying of the New Testament over the centuries. Upon realizing this, “the floodgates opened.” In Mark 4, for example, Jesus allegedly stated that the mustard seed is “the smallest of all seeds on the earth.” Ehrman knew that this simply was not true. The more he studied the early manuscripts, the more he realized that the Bible was full of contradictions. For instance, Mark writes that Jesus was crucified the day after the Passover meal (Mark 14:12; 15:25) while John says Jesus died the day before the Passover meal (John 19:14).

Ehrman often heard that the words of the Bible were inspired. Obviously, the Bible was not originally written in English. Perhaps, suggests Ehrman, the full meaning and nuance of the New Testament could only be grasped when it was read in its original Greek (and the Old Testament could be fully appreciated only when studied in its original Hebrew) (page 6).

Because of these language barriers and the undeniable mistakes and contradictions, Ehrman realized that the Bible could not be the “fully inspired, inerrant Word of God.” Instead, it appeared to him to be a “very human book.” Human authors had originally written the text at different times and in different places to address different needs. Certainly, the Bible does not provide an an “errant guide as to how we should live. This is the shift in my own thinking that I ended up making, and to which I am now fully committed.”

How pervasive is the belief that the Bible is inerrant, that every word of the Bible is precise and true?

Occasionally I see a bumper sticker that reads: “God said it, I believe it, and that settles it.” My response is always, what if God didn’t say it? What if the book you take as giving you God’s words instead contains human words. What if the Bible doesn’t give a foolproof answer to the questions of the modern age-abortion, women’s rights, gay rights, religious and supremacy, western style democracy and the like? What if we have to figure out how to live and what to believe on our own, without setting up the Bible as a false idol–or an oracle that gives us a direct line of communication with the Almighty.(Page 14). Ehrman continues to appreciate the Bible as an important collection of writings, but urges that it needs to be read and understood in the context of textual criticism, “a compelling and intriguing field of study of real importance not just to scholars but to everyone with an interest in the Bible.” Ehrman finds it striking that most readers of the Bible know almost nothing about textual criticism. He comments that this is not surprising, in that very few books have been written about textual criticism for a lay audience (namely, “those who know nothing about it, who don’t have the Greek and other languages necessary for the in-depth study of it who do not realize there is even any “problem” with the text).

Misquoting Jesus provides much background into how the Bible became the Bible. It happened through numerous human decisions over the centuries. For instance, the first time any Christian of record listed the 27 books of the New Testament as the books of the New Testament was 300 years after the books have been written (page 36). And those works have been radically altered over the years at the hands of the scribes “who were not only conserving scripture but also changing it.” Ehrman points out that most of the hundreds of thousands of textual changes found among the manuscripts were “completely insignificant, immaterial, of no real importance.” In short, they were innocent mistakes involving misspelling or inadvertence.

On the other hand, the very meaning of the text changed in some instances. Some Bible scholars have even concluded that it makes no sense to talk about the “original” text of the Bible. (Page 210). As a result of studying surviving Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, Ehrman concluded that we simply don’t have the original words constituting the New Testament.

Not only do we not have the originals, we don’t have the first copies of the originals. We don’t even have copies of the copies of the originals, or copies of the copies of the copies of the originals. What we have are copies made later-much later. In most instances, they are copies made many centuries later. And these copies all differ from one another, and many thousands of places . . . Possibly it is easiest to put it in comparative terms: there are more differences among our manuscripts and there are words in the New Testament.In Misquoting Jesus Bart Ehrman spells out the ways in which several critical passages of the New Testament were changed or concocted. They are startling examples:

A.) Everyone knows the story about Jesus and the woman about to be stoned by the mob. This account is only found in John 7:53-8:12. The mob asked Jesus whether they should stone the woman (the punishment required by the Old Testament) or show her mercy. Jesus doesn’t fall for this trap. Jesus allegedly states “Let the one who is without sin among you be the first to cast a stone at her.” The crowd dissipates out of shame. Ehrman states that this brilliant story was not originally in the Gospel of John or in any of the Gospels. “It was added by later scribes.” The story is not found in “our oldest and best manuscripts of the Gospel of John. Nor does its writing style comport with the rest of John. Most serious textual critics state that this story should not be considered part of the Bible (page 65).

Read the rest.

No comments:

Post a Comment